By Cat Thomas –

A migrant caregiver, caught on camera in a family home hitting her elderly charge, faced a glare of cameras at a recent news conference while the patient’s family rebuked and condemned her. In the preceding days, the footage, released by the family, had unleashed a flurry of stories characterizing the caregiver as ‘evil’.

The scene does not surprise immigrant worker Mayeth Camutua. Although she does not condone the caregiver’s behavior, she says, the press conference typifies Taiwanese media coverage of the immigrant workforce.

“The caregiver, she was never given the opportunity to talk, to say what she was feeling, why she was doing that,” says Camutua.

Inequality is a matter of everyday life for Taiwan’s migrant workers— employment laws and immigration policy have long treated them as second class, and media representation inevitably shapes public perception and discourse.

Camatua, a Filipina currently employed in a Taoyuan factory, has first-hand experience with the often-inhumane working conditions of migrant caregivers in Taiwan: the exhaustion from being “on duty” 24-7, and the consequent psychological ill-effects that she says can cause someone to act out of character.

She initially came to Taiwan as a caregiver and was allowed to transfer industries after winning an administrative case against her employer for mistreatment and abuse.

In the fast-moving landscape of Taiwanese TV and breaking news, stories about migrant workers frequently make the headlines, often related to infractions of immigration regulations or other laws, or accusations of abuse of their charges. When such stories run, the workers involved are rarely given a right of reply.

An imbalance in access leaves employment brokers and disgruntled employers able to get their viewpoints across at a media conference. The subjects of such reports are at a distinct disadvantage. Taiwan’s inflexible employment regulations require workers to stay with their specified employer unless the employer releases them from the contract or by order of the Ministry of Labor.

Workers are under pressure from employers and brokers, in fear of losing their right to residency or possible detention, and often lack local language skills. The result is one-sided breaking news and follow-up stories.

The caregiver in the case Camatua referenced was brought to a press conference by her broker to apologize to the family, but it was clear, with family members shrilly berating her, that she was not able to freely express her side of the story.

While the TV and breaking news sites often sensationalize stories, prioritizing the views of employers or government agencies over those of the migrants themselves, long form and investigative pieces often employ admirable skill and sensitivity toward both the subjects and the issues that surround the stories.

Widely read media such as Apple Daily, United Daily News, The Reporter, Mirror Media, and CommonWealth feature excellent investigative reporting and long-form articles. Many of these probe the unequal treatment and labor laws that lead to the exploitation of these workers. The PTS (Public Television Service) also runs discussions around related issues with reasonable regularity.

As in other countries, terminology used is a key factor in public perception and discourse.

In 2017, following the death of Nguyen Quoc Phi, a Vietnamese national who was fatally shot by police, the National Immigration Agency changed their description of workers who leave without their employer’s consent from “runaway worker” (逃逸外勞/táoyì wàiláo) to “lost contact migrant worker” (失聯移工/ shī lián yí gōng).

The agency stated that many systemic issues force workers onto this path, and that criminality or wrongdoing ought not to be implied. While this nod toward neutrality has been adopted by some media outlets, “runaway worker” is still used quite widely.

The term “wài láo” (外勞/foreign laborer) is another example among many. Although many reporters and editors deem this a derogatory term that ought to be avoided — opting instead for the more neutral “yí gōng” (移工/ migrant worker) — “wài láo” is still used regularly in media outlets.

The types of stories covered, their framing, and the voices being heard, are also crucial to public perception.

Central Taiwan Correspondent for International Community Radio Taiwan (ICRT) Courtney Donovan Smith watches the local TV news and combs through between 50-100 Mandarin language articles for his weekly news report. He has noticed that reporting angles have adjusted during his decade in the job.

“There has been some improvement, though there is still a way to go,” says Smith, “Earlier on, there was little acknowledgment of the basic humanity of the subjects if they were foreign blue-collar employees, but most coverage now at least nods in that direction.”

In a story about a migrant worker who saved a grateful Taiwanese citizen from a fire, the approach was slightly condescending, Smith says. But in earlier times, “the story wouldn’t have been run at all.”

Taiwan’s changing demographics may explain this change. Taiwan expects to reach super-aged society status by 2025 and is dependent on around 700,000 migrant workers in the blue collar and homecare/nursing sectors.

Without the approximately 230,000 caregivers, many families could not afford care for elders, limiting their ability to work. But domestic caregivers are exempt from minimum wage requirements and often start on a base salary of around NT$17,000 compared to the legal minimum wage of NT$25,250.

Manufacturing—such as Taiwan’s booming silicon chip industry—also relies heavily on the better paid and regulated migrant labor, especially for roles that might be categorized as 3D (dirty, difficult, dangerous). Such workers are covered by the Labor Standards Act, and are technically entitled to the minimum wage, overtime, and regulation of hours and working conditions.

Moreover, second-generation immigrants are increasingly involved in public affairs and politics, raising the profile of immigrants. This combination of societal need and immigrant empowerment appears to be changing the ways in which media outlets represent migrant workers. And there is growing awareness of how the terminology describing migrant workers and story angles reinforce the public’s perception of the workers’ role in society.

CTS Morning News Anchor Sabrina Sung says she has seen changes over the last decade, with migrant workers now more acknowledged as an integral part of Taiwan’s society.

“So, more care is taken with the terms used to describe them in the media,” she says

Improved coverage enables readers to understand, empathize with, and appreciate this vital segment of society.

Mirror Media last March ran a lengthy piece on Filipino beauty pageants, which successfully intertwined themes of social activity, empowerment, homesickness, the challenges of maintaining strong relationships with their children, and reasons for working overseas.

CommonWealth magazine, which Statistica.com lists as the second most-trusted news source in Taiwan after PTS, has an online opinion section that regularly runs stories about positive and negative aspects of the migrant worker experience. These glimpses into everyday working life, volunteer work and hobbies, as well as stories about Taiwan’s generation Z trying to reconnect with the nannies that raised them, help build a rounded picture of the community.

The Opinion Channel Director Yun-chan Liao has dedicated much of her professional life to raising the profile and voice of Taiwan’s Southeast Asian migrants. A former professor at Shih Hsin University College of Journalism, in 2015 she founded Brilliant Time South East Asia-themed bookstore, and she credits the “wonderful and diverse” migrant workers she has met from all over the world as the driving force behind her curation of a section that makes these stories accessible to a local audience.

Earlier media coverage tended to be binary, Liao says, but multiple narratives are slowly emerging in local media. In Liao’s opinion the perception of the role of migrant workers in Taiwan’s mainstream society is changing, from being disposable 工具人 (gōngjù rén/ “tool people”) to fellow humans.

Taiwan’s Ministry of Labor is currently reviewing the Employment Service Act to address the gaps in Taiwan’s workforce by offering a path to permanent residency to a narrow section of skilled workers. Currently most can only stay for 12 to 14 years maximum, and dependents cannot be sponsored.

Liao expects the trends toward a better understanding of migrant workers’ role in society to increase as the program rolls out.

“Taiwanese society is slowly realizing that without the labor support of these 700,000 people, it would be difficult for Taiwan to continue functioning,” says Liao.

Indeed, the situation is desperate —from the point of view of employers at least. In December, CommonWealth magazine ran a 22-page cover story on migrant workers and the challenges facing Taiwan. COVID-19 restrictions saw a six-month suspension of incoming migrant workers, yet there’s increased manufacturing as companies move back from China to avoid U.S-tariffs, on top of the demographic changes.

This has forced Taiwan into a situation where there are insufficient people to fill the roles in factories and homes across the country. Moreover, Taiwan now offers the second lowest wages for industrial work in Asia, making it a less attractive option.

While improvements in media coverage have been seen over the past decade, it remains to be seen if this new state of affairs will encourage more outlets to adjust their framing of stories related to migrant workers.

Camatua, as she enters her sixth year in Taiwan, simply hopes that the media can be fair to workers and investigate stories more thoroughly so that lessons can be learned on all sides when problems arise.

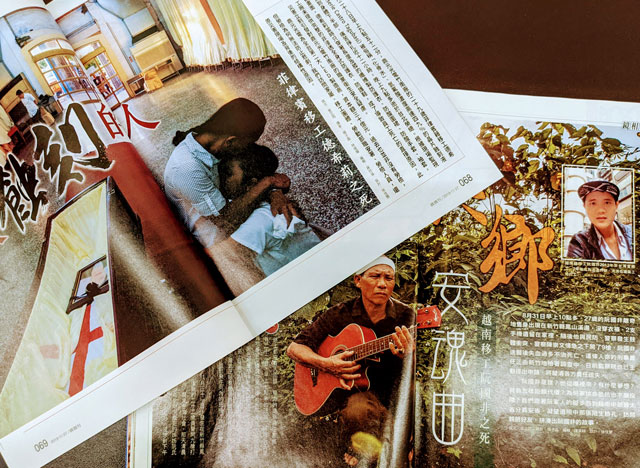

Cover image: CommonWealth Magazine’s cover for the December 2021 issue “No Workers for Factories. No Care for the Elderly. A Future Without Cheap Migrant Workers.” Photo credit: Cat Thomas